Brains are like sponges, slurping up new information. But sponges may also be a little bit like brains.

Sponges, which are humans’ very distant evolutionary relatives, don’t have nervous systems. But a detailed analysis of sponge cells turns up what might just be an echo of our own brains: cells called neuroids that crawl around the animal’s digestive chambers and send out messages, researchers report in the Nov. 5 Science.

The finding not only gives clues about the early evolution of more complicated nervous systems, but also raises many questions, says evolutionary biologist Thibaut Brunet of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, who wasn’t involved in the study. “This is just the beginning,” he says. “There’s a lot more to explore.”

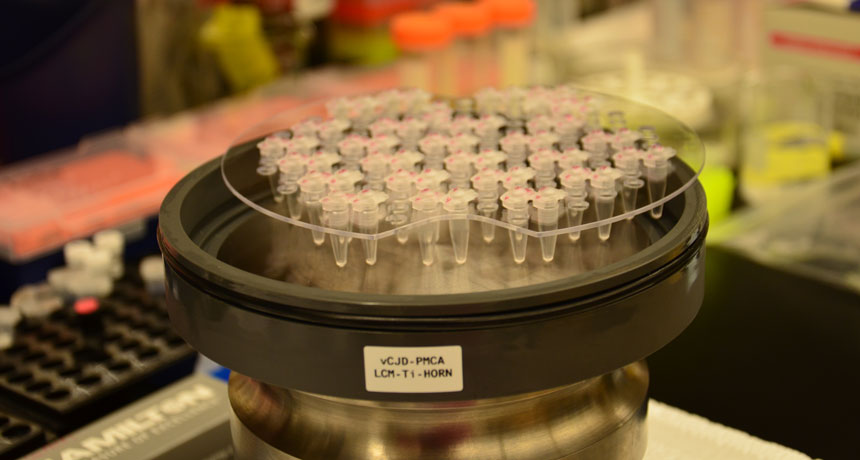

The cells were lurking in Spongilla lacustris, a freshwater sponge that grows in lakes in the Northern Hemisphere. “We jokingly call it the Godzilla of sponges” because of the rhyme with Spongilla, say Jacob Musser, an evolutionary biologist in Detlev Arendt’s group at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg, Germany.

Simple as they are, these sponges have a surprising amount of complexity, says Musser, who helped pry the sponges off a metal ferry dock using paint scrapers. “They’re such fascinating creatures.”

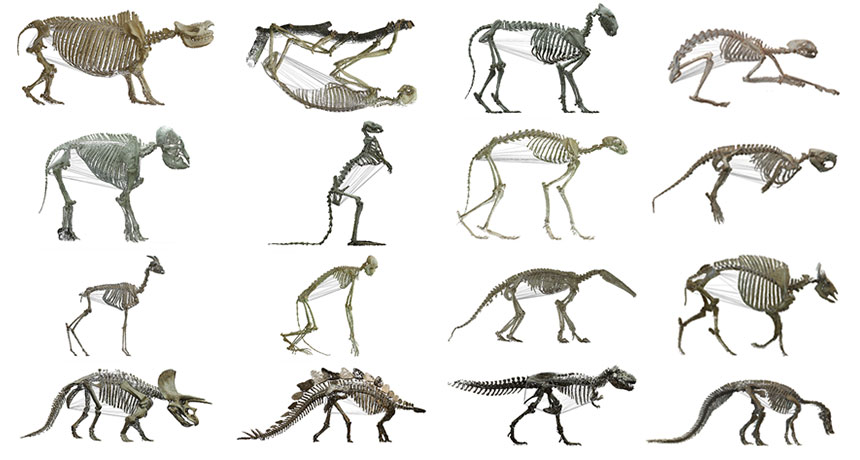

With sponges procured, Arendt, Musser and colleagues looked for genes active in individual sponge cells, ultimately arriving at a list of 18 distinct kinds of cells, some known and some unknown. Some of these cells used genes that are essential to more evolutionarily sophisticated nerve cells in other organisms for sending or receiving messages in the form of small blobs of cellular material called vesicles.

One such cell, called a neuroid, caught the scientists’ attention. After seeing that this cell was using those genes involved in nerve cell signaling, the researchers took a closer look. A view through a confocal microscope turned up an unexpected locale for the cells, Musser says. “We realized, ‘My God, they’re in the digestive chambers.’”

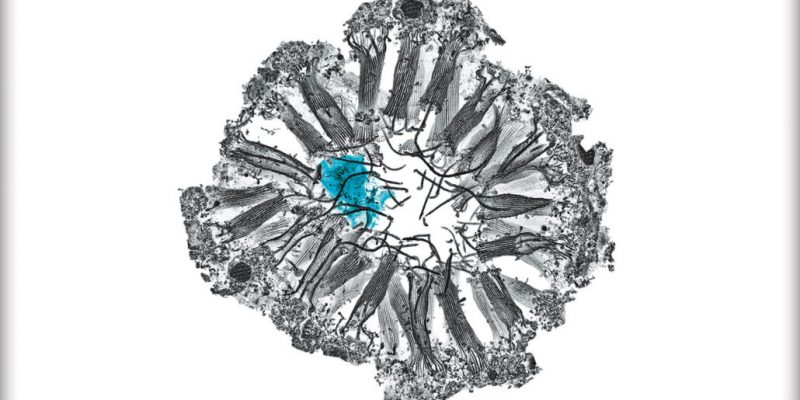

Large, circular digestive structures called choanocyte chambers help move water and nutrients through sponges’ canals, in part by the beating of hairlike cilia appendages (SN: 3/9/15). Neuroids were hovering around some of these cilia, the researchers found, and some of the cilia near neuroids were bent at angles that suggested that they were no longer moving.

The team suspects that these neuroids were sending signals to the cells charged with keeping the sponge fed, perhaps using vesicles to stop the movement of usually undulating cilia. If so, that would be a sophisticated level of control for an animal without a nervous system.

The finding suggests that sponges are using bits and bobs of communications systems that ultimately came together to work as brains of other animals. Understanding the details might provide clues to how nervous systems evolved. “What did animals have, before they had a nervous system?” Musser asks. “There aren’t many organisms that can tell us that. Sponges are one of them.”