Most fish turned into fishmeal are species that we could be eating

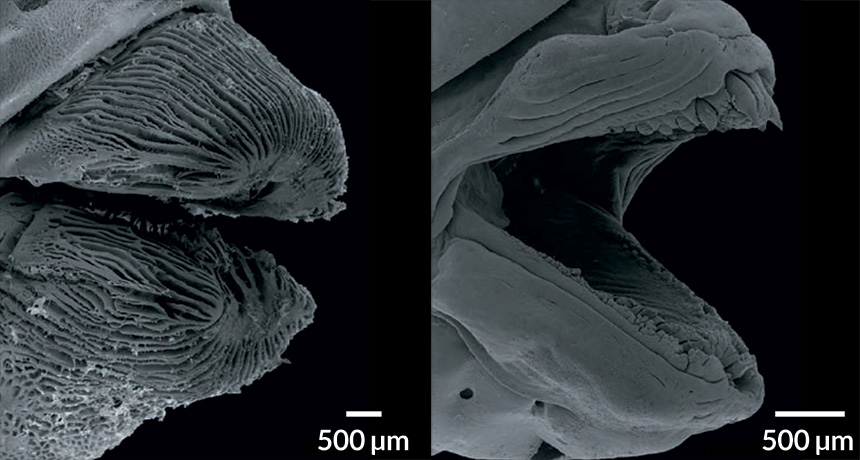

A person growing up in Peru in the 1970s or 1980s probably didn’t eat anchoveta, the local species of anchovies. The stinky, oily fish was a food fit only for animals or the very poor. The anchoveta fishery may have been (and still is, in many years) the world’s largest, but it wasn’t one that put food on the table.

For thousands of years, though, anchoveta fed the people of Peru. It was only when the industrial fishing fleet got started in the 1950s — one that converted most of its catch into fishmeal for feeding other animals — that people lost interest in the fish.

In fact, of the some 20 million metric tons of fish caught annually around the world for uses other than eating, 90 percent are fish that are perfectly good to eat, such as sardines, anchovies and herring, a new study finds.

“Historically, these fish were eaten for human consumption,” but at some point, like the anchoveta, they gained a reputation as being “trash,” notes Tim Cashion, the study’s lead author.

Cashion is a researcher for the Sea Around Us project at the University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Ocean and Fisheries, and he and his colleagues have been collecting data to illuminate the impact of fisheries on marine ecosystems. Cashion spent a year tallying up fishery catches around the world from 1950 to 2010, figuring out who caught which species and where the fish went after it was taken out of the sea.

About 27 percent of ocean fish caught became fishmeal or fish oil. Those products were used to feed farmed fish or used in agriculture, for purposes such as feeding pigs and chickens. And most of the fish species were either food-grade (used as food somewhere in the world) or prime-food-grade (widely accepted as food everywhere), Cashion and his colleagues report February 13 in Fish and Fisheries.

“There could be a better use of these fish,” says Cashion. Instead of feeding fish to fish, the fish could feed people, especially those who lack access to high-quality sources of protein.

But the reason why that doesn’t happen is a combination of economics and regulations. In many places, and for many fish, a fisherman can get more money for his catch if he sells it for fishmeal than if he sells it to the locals for their meals. And in Peru, those economic incentives have combined with a 1992 law and more-recent regulations to keep anchoveta off locals’ plates — despite increased demand brought on by efforts to change the fish’s poor reputation. (These included segments on a popular TV food show.)

By law, the industrial fishing fleet in Peru can only sell anchoveta for fishmeal. Only smaller, artisanal fleets can catch anchoveta for people to eat and can’t legally sell their catch for fishmeal — but the higher price offered by the fishmeal plants means that many do. As a result, the amount of anchoveta that people in Peru consumed dropped by more than half from 2011 to 2014, despite more people actually wanting to eat the fish.

But a change in how the anchoveta are handled could satisfy both the need to feed the Peruvian people and supply the fishmeal industry, Santiago de la Puente of the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries and colleagues note February 15 in Fish and Fisheries. A ton of anchoveta caught for canning yields 150 kilograms of fish in the can and 600 kilograms of heads, guts and other bits that are perfect for fishmeal. If all the anchoveta were diverted through the canning industry, the researchers calculate a net yearly benefit of 40,000 jobs, $351 million in additional revenue and 40 kilograms of nutrient-rich, tasty fish for every person in Peru.