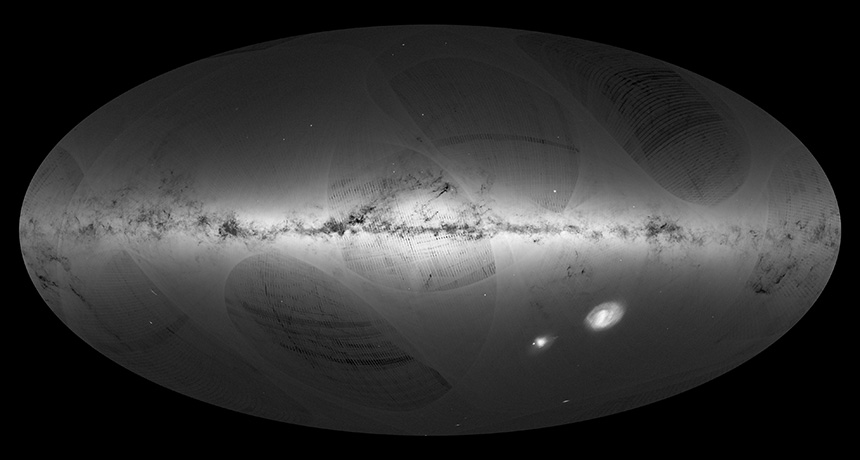

Gaia mission’s Milky Way map pinpoints locations of billion-plus stars

A new map of the galaxy, the most precise to date, reveals positions on the sky for over 1 billion stars both within and beyond the Milky Way.

This new galactic atlas, courtesy of the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft, also provides distances to roughly 2 million of those stars, laying the groundwork for astronomers who want to piece together the formation, evolution and structure of the Milky Way.

“This is a major advance in mapping the heavens,” Anthony Brown, an astrophysicist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, said September 14 at a news briefing. “Out of the 1 billion stars, we estimate that over 400 million are new discoveries.”

There are no major cosmic revelations yet; those will develop in the months and years to come as astronomers pore over the data. This catalog of stars is just a first peek at what’s to come from Gaia, which is spending five years gathering intel on a wide variety of celestial objects.

The final survey will eventually provide a 3-D map of over 1 billion stars. It will also chart positions of roughly 250,000 asteroids and comets within the solar system, 1 million galaxies, and 500,000 quasars — the blazing cores of galaxies lit up by gas swirling around supermassive black holes. Mission scientists also expect they will turn up over 10,000 undiscovered planets orbiting other stars.

“It’s a very democratic mission,” said project scientist Timo Prusti. “Anything that looks like a [point of light] gets caught up and observed.”

Gaia launched on December 19, 2013, and eventually settled into its home about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth on an orbit that follows our planet around the sun (SN Online: 12/19/13). Regular science observations started in July 2014. This first data release, described in a series of papers being published online starting September 14 in Astronomy & Astrophysics, contains data obtained through September 2015.

The spacecraft repeatedly scans the sky with two telescopes pointed in different directions. To make the 3-D map, Gaia measures each star’s parallax, a subtle apparent shift in the position of the star caused by the changing viewing angle as the spacecraft loops around the sun. By measuring the amount of parallax, and knowing the size of Gaia’s orbit, astronomers can triangulate precise distances to those stars.

With distances in hand, astronomers can figure out how intrinsically bright those stars are, which in turn will help researchers understand how stars evolve. A detailed stellar map could also help chart the Milky Way’s distribution of dark matter, the elusive substance that is thought to make up the bulk of the mass in all galaxies and reveals itself only through gravitational interactions with stars and gas.

One controversy that astronomers are eager to resolve with Gaia is the distance to the Pleiades star cluster, one of the closest repositories of youthful stars. A previous Gaia-like mission, the Hipparcos satellite, came up with a distance of about 392 light-years. Estimates based on simulations of how stars evolve as well as observations from the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based radio observatories pin the Pleiades at about 443 light-years away (SN Online: 4/28/14).

“Clusters give you a sense of the evolution of stars at different ages,” says Jo Bovy, an astrophysicist at the University of Toronto who is not involved with the Gaia mission. “The Pleiades is a nearby cluster that we can study well — it’s one of the cornerstones.” All of the stars in the Pleiades are roughly 100 million years old, and so provide a snapshot of a relatively young stellar age. Nailing down the distance reveals the intrinsic brightness of the stars, which is crucial to understanding how stars develop in their early years.

Gaia appears to be leaning toward the larger distance, Brown said, but there’s still too much uncertainty in the data to say anything definitive. “It’s too early to say how the controversy will be resolved. But Gaia will pin it down.”

The Pleiades distance debate, as well as a clearer picture of how the Milky Way is put together, will have to wait for future data releases from Gaia. The next release is planned for late 2017; the final catalog won’t be available until 2022.

“Those will be much more interesting,” Bovy says. “Then we can actually start using our modeling machinery and see how stars are distributed throughout the galaxy. We can test our understanding of dark matter and our understanding of how the Milky Way formed.”